My 2015 Wish for the Progressive Christian Internet: More Conversation About Justice

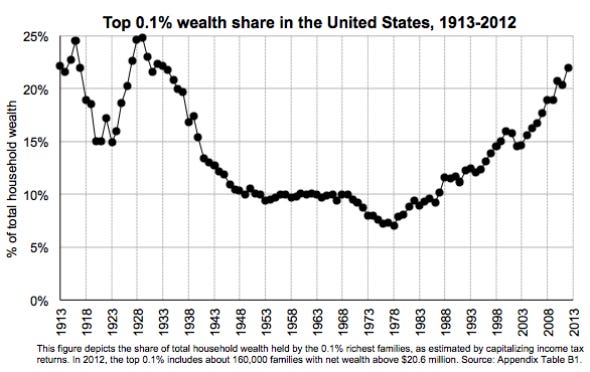

Over at Slate Jordan Weissmann nominates the graph above as the "Best Graph of 2014" documenting "The Rise and Rise of the Top 0.1 Percent."

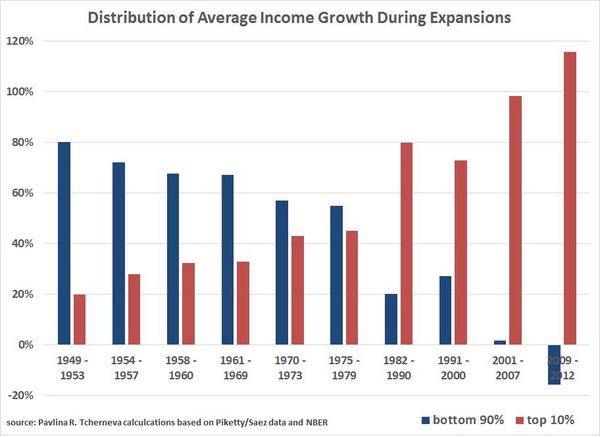

This graph from economist Pavlina Tcherneva has also gotten "best graph of the year" attention:

This graph shows income growth for the bottom 90% compared to the top 10% as each group bounced back after great US recessions. Note how since the 1980s recoveries from recessions (bouncing back) have been disproportionately experienced by the top 10% with the bottom 90% bouncing back from recessions less and less, falling further and further behind.

I never got around last year to blogging about Thomas Piketty's book Capital in the Twenty-First Century. The book is a long and detailed historical analysis of capitalism, but the overarching conclusion and implication of the book are easy to summarize.

The overarching conclusion is this: wealth grows faster than income. Phrased more precisely, capital grows faster than wages.

What this means is that over time capitalism creates increasing inequality between those who possess wealth versus those who earn wages. This is the mechanism--the different growth rates of capital versus income--that creates the "Main Street" (wages/income) and "Wall Street" (wealth/capital) divide.

The implication of this is also simple to summarize: these different growth rates create democratic instability. That is, the inequalities produced by capitalism put pressure and stress upon democracy. By creating economic inequality capitalism fuels class resentment placing increasing strain upon the social contract.

Now, perhaps the mechanisms described by Piketty are at work in the graphs above. Perhaps not. Piketty and his book have received a great deal of pushback and criticism. Regardless, and following the argument of Piketty, I think it safe to say that the graphs above do point to pressure and stress that our current economic arrangement is placing upon the democratic social contract. As wealth grows and grows at an ever accelerating rate wages continue to remain stagnant. That divergence, if it continues, is not sustainable and will fray to the breaking point the social fabric of America. The middle-class is rapidly evaporating in America. And when the middle-class evaporates the democratic and social infrastructure that holds us together evaporates.

What to do? Again taking a cue from Piketty, democracy has to reassert itself to reduce the gap between wages and wealth. This can happen in a variety of ways, all of them controversial and political quagmires. But all have the same goal: democratic redress of the inequalities produced by capitalism. Throughout its history America has had to do this work. And if Piketty is right that work never ends. It's time to do some more of it.

Now I'm sure politically conservative readers will have a range of negative reactions to everything I've just written. We'll just have to agree to disagree. What I'd like to do is end this post with some comments for my more liberal and progressive Christian readers looking forward to 2015.

The year that was 2014 for the progressive Christian Internet was a year that focused a great deal upon the oppressions related to race, gender and sexuality. Conversations about "checking privilege" abounded. Great effort was spent upon "centering," especially centering those for whom various oppressions "intersect" and stack up to create extremes of marginalization.

I applaud and have contributed to all those conversations. And yet, often missing from the progressive Christian Twitter and blogosphere in 2014 was a similarly robust, broad, sustained and energized conversation about class, labor, economic inequality and poverty.

For example, in discussions about racial reconciliation, centering and checking privilege many progressive Christians fail to attend to the issue of class and how it affects race relations. The issues in places like Ferguson have as much to do with economics as they have to do about race. I think it's vital that we check privilege and center voices at the intersections of oppression, but unless we deal with the structural economic issues our social media activism can devolve into to moral signaling and posturing.

I believe in and participate in all sorts of efforts aimed at reconciliation within my faith tradition (we have the same racial segregation on Sundays as many traditions do). And a pressing concern in these conversations is justice. And justice, as was pointed out to me recently by a group of African-American church planters, is fundamentally an economic issue.

To give a concrete example. I think it is critical and important to note how many women or persons of color are included as speakers at Christian events and conferences. We should take note and criticize when the speaking slate is full of white men. But let's not miss the forest for the trees. We can create an inclusive, diverse and multicultural event that de-centers and checks white privilege. But unless those de-centering and privilege checking efforts are leveraged toward addressing economic inequality we remain a far cry from justice.

Symptomatic of this is how progressive Christian activism can become a largely linguistic activity, focused upon policing, correcting and calling out how and when people speak and write (or don't speak and write) on social media. Progressive Christian activism is often strangely decoupled from the concrete particulars of economic policy. Which is to say that progressive Christian activism is often failing to have a conversation about justice biblically conceived.

I take my cue here from Martin Luther King, Jr.. In the wake of the historic Civil Rights legislation passed in 1964 and 1965 the plights of most black Americans remained largely unchanged. Thus the disillusionment post-1965 that grew among the black population and civil rights activists, fueling race riots and the rise of the Black Power movement. So much had changed with the demise of Jim Crow but in so many important ways nothing had changed at all. And King saw economic inequality as the root problem. Thus, after 1965 King increasingly focused upon economics as the key factor in race relations. King was assassinated in the midst of organizing the Poor People's Campaign.

As King saw more and more clearly, there can be no "racial reconciliation" without (economic) justice.

I fear many progressive Christians are forgetting King's message and hard-won insight. Let us be students of history. Let us listen to what Dr. King was teaching in 1968. Let us remember the role of the charkha in the teachings of Gandhi. Let us go back to the socioeconomic origins of South American liberation theology. Thousands of words have been shared on progressive Christian social media about privilege, centering, diversity and reconciliation with very little associated conversation about economic justice.

Calls to "check privilege" and "center the margins" become ciphers for tolerance rather than clarion calls for justice when they are disconnected from the economic forces driving income and wealth inequality. Issues of race and class need to be intimately and repeatedly connected in these conversations. They rarely are.

So that is my wish for the progressive Christian Internet in 2015. Alongside and informing conversations about centering, privilege, diversity and reconciliation let us have more conversation about class. More conversation about wages. More conversation about labor. More conversation about economic inequality. More conversation about poverty.

More conversation about justice.